Budding Hydra

In Greek mythology, the Hydra was a many headed water serpent with deadly breath. The second task of Hercules was to kill this beast, a difficult feat since each time one head was chopped off two more grew in its place. Although hydras, which belong to the phylum Coelenterata, are not quite so dreadful, their appearance and reproductive ability are reminiscent of the mythological creature of the same name.

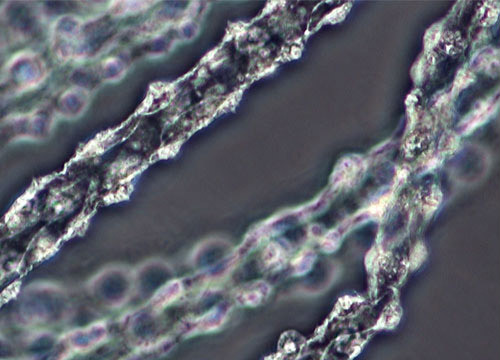

Negative

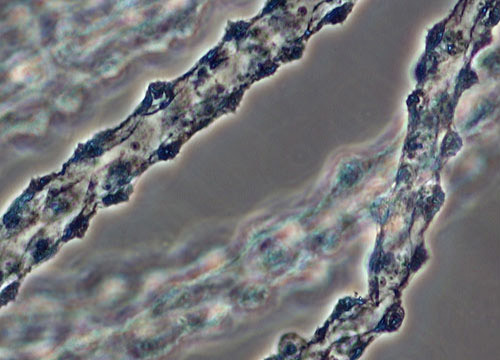

Negative

Positive

Positive